The Grapes of Wrath

Overview

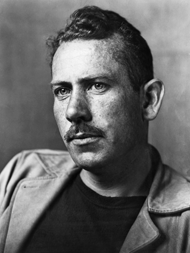

John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath is not merely a great American novel. It is also a significant event in our national history. Capturing the plight of millions of Americans whose lives had been crushed by the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression, Steinbeck awakened the nation's comprehension and compassion.

Written in a style of peculiarly democratic majesty, The Grapes of Wrath evokes quintessentially American themes of hard work, self-determination, and reasoned dissent. It speaks from assumptions common to most Americans whether their ancestors came over in a stateroom, in steerage, or were already here to greet the migrants.

"Literature is as old as speech. It grew out of human need for it, and it has not changed except to become more needed." —from Steinbeck's Nobel Prize speech

Overview

John Steinbeck's The Grapes of Wrath is not merely a great American novel. It is also a significant event in our national history. Capturing the plight of millions of Americans whose lives had been crushed by the Dust Bowl and the Great Depression, Steinbeck awakened the nation's comprehension and compassion.

Written in a style of peculiarly democratic majesty, The Grapes of Wrath evokes quintessentially American themes of hard work, self-determination, and reasoned dissent. It speaks from assumptions common to most Americans whether their ancestors came over in a stateroom, in steerage, or were already here to greet the migrants.

Introduction to the Book

Can a book top the bestseller list, win a Pulitzer Prize, save lives, and still be underrated? If that book is The Grapes of Wrath (1939), the answer is most definitely yes. For too long, Steinbeck's masterpiece has been taught as social history, or dismissed as an "issue novel." It's both these things, of course, but before all that, it's a terrific story. The characters fall in love, go hungry, lose faith, kill, live, and die with an immediacy that makes most contemporary novels look somehow dated by comparison.

The novel begins with young Tom Joad's return home from a prison term to find his family's Oklahoma farmstead in ruins and deserted. He soon locates his relatives nearby, preparing to leave their land for the promise of a new life in California. We follow their travails and partake of their hopes, only to share in their disappointment when California's agricultural bounty makes no provision for them except as occasional day laborers. Under the strain, the Joad family gradually comes apart until only a struggling remnant survives. In an unforgettable conclusion, we leave these few bereft of everything except their imperishable humanity.

Along the way, we meet a cast of characters as overstuffed as the Joad family's panel truck. From the indomitable matriarch Ma Joad to the starving old man in the book's final scene, Steinbeck gives them the individuality that an unforgiving economy threatens to cost them. In a remarkable balancing act, they represent those displaced by the Depression without ever subsiding into mere symbols.

And that's only half the story. The Grapes of Wrath is at least two books in one. Roughly half the chapters tell the saga of the Joads, while the other half have no continuing characters, and hardly any named people at all. These "generals," as Steinbeck usually called his interchapters, emphasize the point that the Joads stood in for all the Depression-era westward migrants. He felt a greater sense of responsibility to his material in this book than any other, and he was determined that no reader mistake the Joad's travails for an isolated case.

Steinbeck wrote The Grapes of Wrath in an amazing five-month burst of productivity. His first marriage was starting to crack, and every day brought new entreaties from good causes to chair this committee or attend that benefit. In retrospect, the days that birthed the novel stand testament to perhaps its greatest theme: the dignity of hard work, done by hand and beset by doubt, with all one has, and for others to share.

Major Characters in the Book

Tom Joad

Just released from prison as the novel begins, Tom is quick to fight but fundamentally decent. He loves his family and finds himself gradually radicalized by its slow disintegration.

Ma Joad

Blessed with the ability to improvise a meal or a bed from the barest of provisions, Ma's strength and resilience ultimately prove her the true bulwark of the family.

Jim Casy

A defrocked preacher turned itinerant philosopher, Jim gives voice to much of Steinbeck's own mistrust of organized religion and belief in social justice.

Rosasharn Joad Rivers

Under Ma's influence, Tom's sister matures from a fairly insufferable expectant mother into a woman capable of one of the most memorable sacrifices in American literature.

Uncle John Joad

Uncle John is a sometime drunk who holds himself responsible for his late wife's death. His most memorable scene comes when he sets the youngest Joad adrift in the river to bear mute witness against the suffering of all the Dust Bowl migrants.

Al Joad

Al becomes suddenly indispensable to his family, since he's the only one who can keep their precious truck running. Unfortunately, some things are even more gripping to a teenage boy like Al than an automobile—for example, teenage girls.

The "man who lay on his back"

Never named, this minor but indelible character shares the novel's final, unforgettable tableau with Rosasharn. Like the prostrate underclass he represents, he needs help to survive but is too proud to beg.

How The Grapes of Wrath Got Its Name

"Battle-Hymn of the Republic"

by Julia Ward Howe

Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord:

He is trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored;

He hath loosed the fateful lightning of his terrible swift sword:

His truth is marching on.

Julia Ward Howe (1819-1910) published her popular Union song, "Battle-Hymn of the Republic," in the Atlantic Monthly in 1862. Carol Steinbeck thought the first verse's phrase "the grapes of wrath" would be the perfect title for her husband's epic novel.

- Why would Steinbeck weave general chapters—often called "interchapters"—with the Joad story? Is the alternation consistent, or are there deviations?

- The turtle in Chapter 3 is often interpreted as a parable or symbol. What do you think?

- In prison, Tom "learned to write nice as hell." Meanwhile, Casy leaves the pulpit to "hear the poetry of folks talkin'." How does Steinbeck strike a balance between the more metaphorical, image-laden prose of "birds an' stuff" and "the poetry of folks talking"?

- Casy says, "I ain't preachin'. Preachin' is tellin' folks stuff. I'm askin' 'em." Do you feel Steinbeck is doing either in The Grapes of Wrath?

- At which points in the book does the power in the family gradually shift from Pa to Ma?

- Where do Grandpa and then Grandma die? What might this suggest about where they ultimately do or don't belong?

- What enduring piece of American writing does Ma's line—"Why, we're the people"—remind you of? How could this be ironic?

- What sorts of things happen by rivers in the novel? Why might that be?

- As Casy goes to jail, "On his lips there was a faint smile and on his face a curious look of conquest." And in the novel's last sentence, Rosasharn's "lips came together and smiled mysteriously." Why do both characters leave the novel with a smile?

- Steinbeck is known for creating some of the most memorable friendships in American literature. How does Casy serve as a role model for Tom Joad, and Ma Joad for Rosasharn?

- Steinbeck's writing was influenced by the cadences and themes of the Old Testament. How does the plight of the Joad family parallel the Israelites in Exodus? Do the Joads receive their Promised Land?

- Why do you think this novel continues to have such wide, popular appeal? Is its message still relevant today?