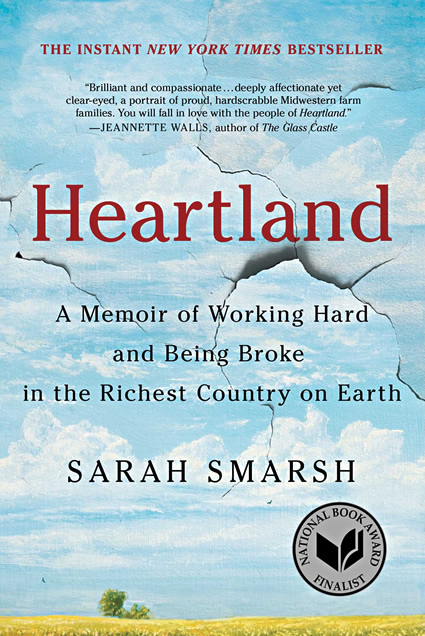

Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth

Overview

A finalist for the National Book Award and winner of the Chicago Tribune Literary Prize, Heartland: A Memoir of Working Hard and Being Broke in the Richest Country on Earth is a “deeply humane memoir that crackles with clarifying insight” (New York Times Book Review). Sarah Smarsh shares stories of her family in rural Kansas and her childhood in the 1980s and ’90s while offering “an unsentimental tribute to the working-class people Smarsh knows—the farmers, office clerks, trash collectors, waitresses—whose labor is often invisible or disdained” (NPR). “If you’re working toward a deeper understanding of our ruptured country, then Sarah Smarsh’s memoir and examination of poverty in the American heartland is an essential read” (Refinery29). “What this book offers is a tour through the messy and changed reality of the American Dream, and a love letter to the unruly but still beautiful place [Smarsh] called home (Boston Globe). It is “an important book for this moment” (EntertainmentWeekly.com).

“The defining feeling of my childhood was that of being told there wasn’t a problem when I knew damn well there was.” — Heartland

Equal parts personal narrative and cultural analysis, Sarah Smarsh’s memoir Heartland examines her childhood on a farm 30 miles west of Wichita, Kansas, mapping family histories against the rapidly changing landscape of class and labor in the United States during the latter part of the 20th century. Addressed to Smarsh’s unborn child, Heartland traces the many threads of history that led her family to Kansas, articulating “what no one articulated for me: what it means to be a poor child in a rich country founded on the promise of equality” (p. 2).

In Heartland, the personal is inextricable from the institutional. Smarsh’s German ancestors first migrate to Kansas under the expansionist promises of the Homestead Act. Decades later, Smarsh’s Grandpa Chic plows the same land, coaxing wheat from soil as President Jimmy Carter issues a sober warning to a nation caught in the thrall of consumerism. In the 1980s under President Ronald Reagan, small businesses shutter and family farms are foreclosed on in droves, accelerating the economic demise of American workers. “That was the climate I came up in,” Smarsh writes. “All around us things were closing…but we held on” (p. 88). Throughout the memoir, Smarsh pays tribute to the generations of laborers that teach her to “hold on”: her Grandpa Arnie, a farmer with dancing feet and a laugh that can heal; her Grandma Teresa, whose resolute strength gives shape to Smarsh’s dreams; her father Nick, a quiet builder working to lay the foundation for his own home someday; her mother, Jeannie, a brilliant dreamer with a distant heart; and her Grandma Betty, a fierce fighter with a boundless capacity for empathy.

In sharing her family’s stories, Smarsh deepens conventional narratives about class and labor and interrogates assumptions about American wealth: who holds it, who takes it, whose labor makes it possible. Within these stories are lethal hardships: unsafe job conditions, untreated medical conditions and a lack of affordable and accessible health care, abusive relationships, and impossibly high hoops required to receive federal aid or just to keep a family together. By telling the story of her life and the lives of the people she loves, Smarsh challenges us to look more closely at the class divide in our country, a divide that “causes us to see one another as stereotypes” (p. 251).

Though Heartland offers a searing indictment of the systemic inequalities underpinning the American Dream, it is not a memoir solely of hardship. Instead, the stories contained within it show the resilience of joy, the hard work of community, the kind of love that inoculates—not against the challenges and pain of poverty, but against the oft-told myth that those who earn less are somehow worth less. “In a country where personal value is supposed to create wealth, it is easy for a poor person to feel himself a bad one,” Smarsh notes near the end of the book. “The greatest fortune of my life is that I knew they were wrong” (p. 282).

- In the first pages of the book, Smarsh writes that she was young during a time when “you could grow up relatively innocent of your own image” (p. 12). What did she get right and wrong about her own image? What image did you have of yourself when you were young in the context of where you grew up? Has that image changed with time? How do you think it influenced your childhood?

- Throughout her childhood, Smarsh and her family didn’t think much about class, as it “didn’t exist in a democracy like ours…at least not as a destiny or an excuse” (p. 29). When the concept of class did come up, on the news for example, they assumed they were in the middle class, “not poor, but not rich” (p. 28). What forces were behind these attitudes and assumptions? When did you first become aware of class as a concept? Did your perception of class change over the course of your life? If so, what prompted that change/those changes?

- In the second chapter of the book, “The Body of a Poor Girl” (p. 44), Smarsh writes about the physical dangers of poverty, and the home remedies that her family relied on to heal: a decade-old dropper of iodine for a cut, a tub of cold water for a fever, bed rest for postpartum bleeding. “The medical industry worked by naming ailments and prescribing medicine, but the sort of healing we knew operated in mystery,” Smarsh writes. “We didn’t know the word ‘placebo’ but figured that’s all survival ever was…Mind over matter” (p. 73). What did you make of Smarsh’s family’s experience with the U.S. health care system? How might these experiences have been different in a different place? During a different time? What factors have affected your own experiences with healing and health care?

- Across Heartland, Smarsh draws a connection between society and policymakers’ abstract valuations of labor and the real consequences those decisions have for undervalued workers. “Work can be a true communion with resources, materials, other people. I have no issue with work. Its relationship to the economy—whose work is assigned what value—is where the trouble comes in” (p. 43). How does Smarsh unpack this statement? Think about the kinds of labor you encounter in your day-to-day life. Which jobs are more valued? Less valued? By whom? Why?

- On p. 81, Smarsh recounts a saying she once read: “what you don’t transmute, you will transmit.” What does each member of her family transmute over the course of their lives? What do they transmit to their children and other loved ones? Can you think of an example of something in your life that has been transmuted and/or transmitted?

- Throughout the book, Smarsh ascribes to family members certain roles, influences, hurdles, attitudes, and ways of dealing with tough circumstances based on their gender. Can you find examples of how and why the men in her life acted differently than the women? Can you find examples of how she and the women in her life acted a certain way because of the actions of the men?

- Many of Smarsh’s experiences growing up are particular to her setting, i.e., rural Kansas. If you were to break that down, what experiences might you attribute to Kansas or the Heartland in particular, and what might you say could apply to rural communities anywhere in the country?

- On pages 129-130, Smarsh asks a number of questions that ultimately pose a larger question about our society’s sense of morality. “If you work every day and still can’t afford what you need, is it worse to steal a little from a big store owned by billionaires than to be a billionaire who underpays his employees? Is it worse to do business under the table with a couple hundred bucks than to keep millions of dollars in an offshore bank?” How would you answer these questions?

- Across the book, transience figures heavily in Dorothy, Betty, and Jeannie’s lives: a legacy they pass onto Smarsh’s own childhood. “By the time Jeannie started high school, they had changed their address 48 times,” Smarsh surmises (p. 7). By ninth grade, Smarsh herself had attended eight schools (p. 194). What do you think the family’s transience meant to Nick, Jeannie, Smarsh, and Matt? What is lost when a life is spent in transience? How did Smarsh cope?

- After Arnie’s death, his farm equipment is sold at auction to farmers from around the county. There, “in the greatest gesture of respect, they bid high,” Smarsh writes. “In a rare act, they had driven a price up, rather than down…they knew what a person’s life was worth” (p. 270-271). Can you find other instances in the book when community members stepped up to support and value each other? Can you think of similar examples within your own community?

- When Smarsh entered college, she realized that the distance between her experiences and the experiences of her classmates was a deeper rift than she’d previously understood. “There are so many complicated reasons why so few people cross a socioeconomic divide in any lasting way, but one of the reasons is simple: it is a painful crossing” (p. 261). What were the sources of pain for Smarsh during this period of “crossing”? How might these challenges have been alleviated: by the institution, by her peers, by the higher education system in the United States more broadly?

- The daughter of generations of teenage mothers, Smarsh addresses Heartland to her own hypothetical, unborn daughter, August: the invisible child that could have made her an invisible teenage mother. Why do you think she chose to present her memoir in this way? How did this structure affect your experience as a reader? How might the stories in Heartland have been told differently if they had been written to another family member?

- Smarsh describes her adult life as a “bridge between two places: the working poor and ‘higher’ economic classes. The city and the country. College-educated coworkers and disenfranchised loved ones. A somewhat conservative upbringing and a liberal adulthood. Home in the middle of the country and work on the East Coast” (p. 247). How can we better support the hard work of those bridging these divides? How can we—as individuals and as a society—build more bridges of empathy?

Source material for Heartland discussion questions from Simon and Schuster