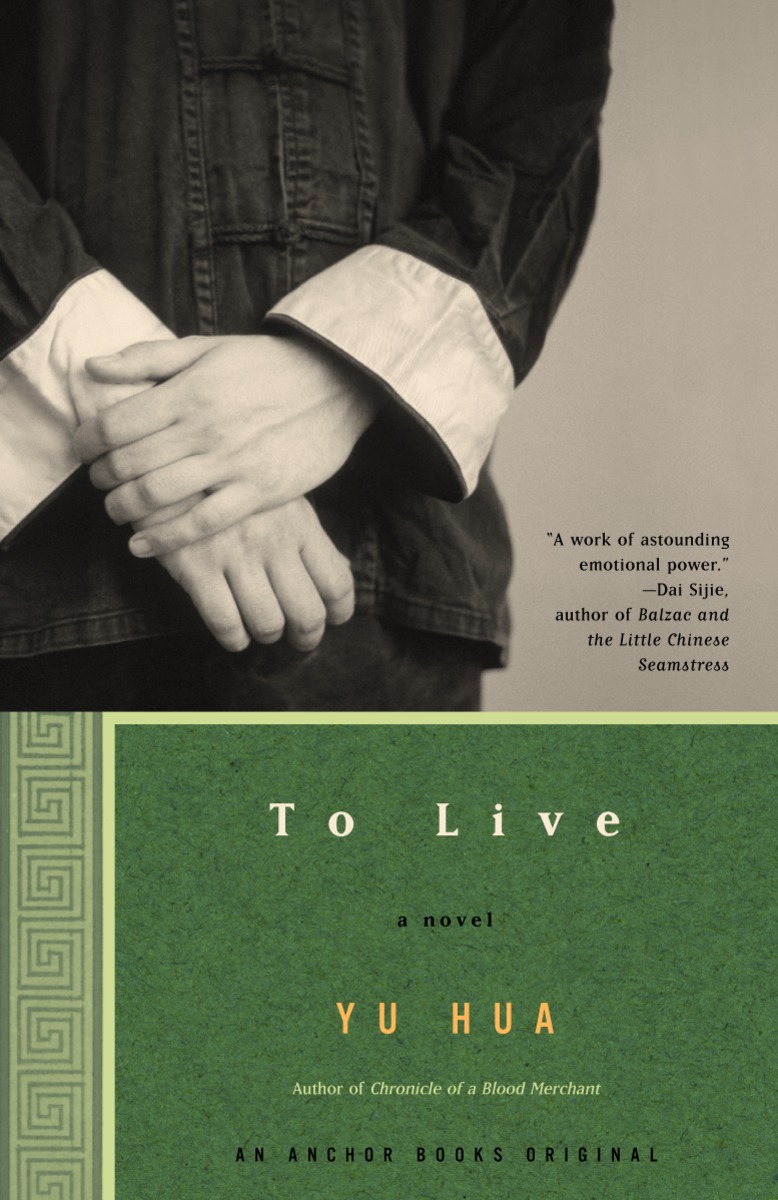

To Live

Overview

Yu Hua is one of China's most well-known authors and his bestselling novel, To Live, has been named one of China's ten most influential books of the last decade. The novel was made into a critically acclaimed film of the same name with China's best-known actress. It tells the poignant tale of a man's transformation from the spoiled son of a rich landlord to an honorable and kindhearted peasant as he and his family endure the ravages of war and starvation. Yu explains in a postscript that the idea for the novel came after he was deeply moved by an American folk song called "Old Black Joe" about a slave who lived through decades of hardships yet was still kind. "Though unmistakably Chinese," writes author Ha Jin, Yu's novels "are universally resonant."

"Just as a mother beckons her children, so the earth beckoned the coming of night." —from To Live

Introduction

"When I write there is a constant voice in my ears. Sometimes I hear laughter, sometimes I hear sobs, sometimes I hear sighs, sometimes I hear myself." — Yu Hua in Modern Chinese Literature and Culture

Although it was initially banned in China, the internationally award-winning epic novel To Live, which was first published in 1993, is now considered to be one of the country's most influential books, with millions of copies in print. Called a "Chinese Book of Job" by the author Wang Ping, it tells the poignant story of a man's transformation from a mean, selfish wastrel to a devoted husband and father trying desperately to keep his family alive during the worst famine in Chinese history and a time of dramatic political and social change. Spanning four decades of modern Chinese history and written in stripped-down prose with a sensitivity to the dialogue and details of everyday life, the novel is tragic and filled with pain, but it is also a tale of endurance, humility, beauty, love, and ultimate redemption.

Fugui is the brash son of a wealthy land-owning family who, at the beginning of the novel, is unfaithful and cruel to his wife, Jiazhen. When he gambles away his family's entire fortune, dragging his mother, father, pregnant wife, and young daughter into poverty, he sets into motion a lifetime of suffering that will soon illuminate for him the error of his ways. He is forced into the Nationalist army, whisked away to fight with no opportunity to tell his family where he has gone. Much later, he returns home to find that his mother has died, and that his beloved and spirited daughter, Fengxia, has been stricken with a fever rendering her deaf and unable to speak. Now a poor peasant farmer, Fugui struggles to understand his sensitive son, Youqing, and as time passes and the family endures more and more hardships, Fugui comes to be filled with gratitude and respect for his stoic wife. Yet, as Fugui's capacity for love and his understanding of others grow, calamities continue to strike.

Fugui's story is told in his own voice to a traveling folk song collector, whom he meets later in life while working with his ox in the fields. In a postscript to the book, Yu says that he was inspired to write To Live after hearing "Old Black Joe," an American folk song about a slave who lives a harsh life but still views the world kindly. Old Black Joe and Fugui could not be more different given their cultural experiences, he explains, but they are both human. This is what makes literature magical, he says, adding that he learned about himself from reading novels by William Faulkner, Toni Morrison, and National Hawthorne.

Despite its epic breadth and the harrowing tragedies at its core, To Live is fast-paced, laced with Yu's signature humor and frankness. Prior to being published in book form, To Live was serially published in the Shanghai literary journal Harvest, which is where the famed Chinese film director Zhang Yimou first came across it. After staying up all night to read it, Zhang resolved to make To Live into a film, which premiered in 1994 to international acclaim, winning the Grand Jury prize and the Best Actor award at that year's Cannes Film Festival. The book was also adapted into a television miniseries entitled Fugui in 2005, and brought to the stage in a production by influential Chinese avant-garde theater director Meng Jinghui in 2012. "The theme which is central in much of my writing is ... Chinese people can overcome any difficulty presented to them," Yu told Modern Chinese Literature and Culture. "The Chinese character remains strong."

The book's translator, Michael Berry, was 22 and a senior at Rutgers University when he sent a fax to Yu Hua requesting permission to translate To Live into English. To this day he feels a great sense of gratitude to Yu for entrusting his masterpiece to a young aspiring literary translator.

- Fugui’s story begins with devastating consequences caused by his cruel and selfish behavior. As his life unfolds and his humanity reemerges, what did he learn to value in life? Do you think he ever forgave himself for his actions?

- There are two narratives in To Live: Fugui’s story and the story of the man who meets Fugui while traveling through the countryside collecting folk songs. How do these two points of view affect your reading experience?

- Is Fugui a good father? A good husband? A good citizen? A good community member? What does it mean to be good in these roles during difficult times?

- Were you surprised by the actions and reactions of Fugui’s family throughout the story – his wife, Jiazhen; his daughter, Fengxia; and his son, Youqing?

- Did you know much about Chinese history and culture before reading To Live? If not, what did you learn? If you knew some or much of it, was your understanding of it challenged or expanded by Fugui’s story? What conclusions might you draw about the author’s view of China’s history?

- Throughout Chinese history, there has been a strong patriarchal tradition. After 1949, Mao Zedong enacted policies that were meant to create more equity between the sexes. Did you see these changes reflected in the novel? How did you react to the novel’s portrayal of gender roles?

- In what ways does the story resonate with traditional Buddhist philosophy?

- The novel moves through four decades of modern Chinese history marked by war, famine, political turmoil, and natural disasters. How does the author manage this pacing and still include details of everyday life? What is the effect of a story that covers so much? What are some of the details that surprised you?

- To Live was originally published in serial form in a literary journal. How would your reading experience have been different if you encountered it this way?

- What is significant about the ox that Fugui is left with to plow his fields? What other animals are symbolic of the Xu family and its history and how so? Can you find other examples of symbolism in the novel?

- To Live is a book in translation (from Chinese into English). What might you imagine are the difficulties in bringing a story from one language into another?

- In 1994, Zhang Yimou directed a major motion picture adaptation of To Live. While some elements were faithful to the book, many details were altered. What elements of the story are different in the film? How do these changes affect the overall tone and themes of the story?

- The song collector tells us that Fugui enjoyed thinking about his past, reliving his life “again and again” (p. 45). Why do you think this might be when his life was filled with so much sadness and hardship? If you were Fugui, would you be telling these stories?

- What does it mean to Fugui and his family to live? What does it mean to you?

Photo by Zheng Ye

Photo by Zheng Ye