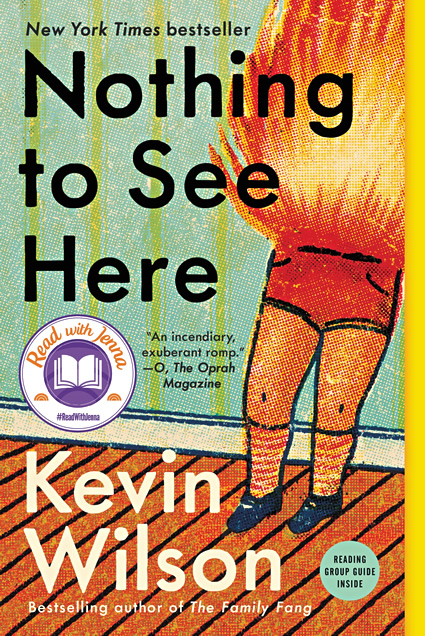

Nothing to See Here

Overview

Kevin Wilson’s bestselling third novel, Nothing to See Here, is the story of 28-year-old Lillian Breaker who accepts a job at a Tennessee mansion to look after—and hide from public view—two ten-year-old twins who burst into flames when they get agitated. Over one hot summer, everything she thought she knew about love, family, and empathy is turned irreversibly upside down. “It’s a giddily lunatic premise, one that author Kevin Wilson grounds with humor and deadpan matter-of-factness….But what dazzles most are the warmly rendered dynamics of an ad hoc, dysfunctional family that desperately wants to work” (USA Today). Wilson “distracts you with these weirdo characters and mesmerizing and funny sentences and then hits you in a way you didn’t see coming” (New York Times Book Review). This “big-hearted” and “bizarre” novel (Chicago Review of Books) is a “funny and touching fable about love for kids, even the ones on fire” (Kirkus).

“They didn’t want to set the world on fire. They just wanted to be less alone in it.” — Nothing to See Here

His third novel and fifth book, Nothing to See Here is a tribute to Kevin Wilson’s ability to chronicle the difficulties of family, to celebrate the odd and the unknown, and to build bodies of joy out of life’s viscera. The novel first finds its narrator, Lillian Breaker, living a pale shadow of the life she’d dreamed for herself as a child. Lillian is working a series of dead-end cashier jobs and living in the dusty attic of her mother’s house when she gets a letter from an old friend from boarding school, pleading for her help. Assigned as roommates at their elite preparatory school, Lillian and Madison became fast—if unlikely—friends as teenagers. After Lillian was unexpectedly forced to leave the school under the shadow of a scandal, the two friends drifted apart. Now, Madison is newly married and searching for a caretaker for her twin stepchildren. She thinks Lillian is the perfect person for the job.

Lillian arrives at Madison’s Tennessee estate to find the eerie placidity of extreme wealth disrupted by something new: the twins spontaneously combust when they get angry or scared, flames igniting from their skin in startling yet beautiful ways. Their fires don’t harm them but they can burn the people around them and leave panic and destruction in their wake, taking aim at adults like their father, a politician, who are ashamed of emotions that are too big, too visible. “Since I was a kid I’ve been obsessed with spontaneous human combustion,” Wilson told the New York Times. “Sometimes I’d be afraid I might burst into flames and other times I wanted to be a human torch. I wanted to manifest my anxiety physically. But what I’m always trying to figure out with my writing is, how can I create a story where people survive dark things? I don’t want anyone to ever get hurt.”

Lillian is an “appealingly forthright oddball, part insecure waif, part foul-mouthed basketball-playing tough, part Julie Andrews as Maria von Trapp” (NPR). Struck by the twins’ fierce loneliness—an echo of her own—she resolves to give the twins the best possible summer and teach them how to cope with their condition, her unruffled persistence breaking through the twins’ wariness. In time, she comes to love her charges and the small family they create.

Through Lillian’s eyes, Wilson paints a world where people not only survive but bloom into technicolor, made vibrant through love. “They stood there, burning. And I was happy,” Lillian writes near the end of the book. “I knew they were okay. I knew that they couldn’t be hurt. The grass turned black at their feet, and the air around them turned shimmery. It was beautiful. They were beautiful” (p. 214).

- On the surface, the title of Kevin Wilson’s novel, Nothing to See Here, is amusing given that the story is about two twins who can do something so unbelievable that few would be able to look away. It also signals that there will be plenty more humor in the pages to come. But as with most humorous stories, there is complexity beneath the comedy. What else could you say about the title? Can you find other examples in the novel that sought to make you laugh while hinting at a deeper emotion?

- Lillian and Madison first meet at Iron Mountain Girls Preparatory School, where Lillian makes a sacrifice for Madison that results in Lillian losing her scholarship and leaving the school. What meaning does that sacrifice hold for Lillian? For Madison? Does its meaning change over the course of the book?

- There is a moment early on during Lillian’s stay at the Roberts’ home where she marvels at how easily she has been absorbed into the rhythms of family life. “It made me think that wealth, as of course I already knew without firsthand experience, could normalize just about anything” (p. 57). What do you think she meant by that? What roles do wealth and social capital play in the book? How do they affect Lillian’s actions and perceptions, both at the beginning of the story and at the end?

- What does it mean to Lillian to be a good parent? What does it mean to other characters in the novel? What does it mean to you?

- When she first gets to know the twins, Lillian says, “I knew how much of myself I was going to unfairly place in them” (p. 80). Could she have helped it? Should she have tried harder to avoid doing it? Can you think of other examples in the novel when parents and caretakers projected preconceived notions onto their children? What was the result?

- When Lillian first meets Bessie and Roland, she is most surprised to realize that their hair remains un-singed when they combust. “I don’t know why…their bad haircuts remaining intact was the magic that fully amazed me, but that’s how it works, I think. The big thing is so ridiculous that you absorb only the smaller miracles” (p. 75). Can you think of other details that Lillian processes to help her understand her situation and the people around her? Has that happened in your life, when you’ve focused on small details because the larger, unexplained event was too hard to process?

- In the novel, many people attempt to diagnose the twins’ condition, or to identify a method to control or “cure” their fire. What are some of the methods put forward? What might these methods reveal about each of the people who suggest them?

- Both Madison and Lillian have estranged relationships with their families, but frequently reference their parents when they consider their own roles as caretakers. “My mom had once told me that being a mother was made up of ‘regret and then forgetting that regret sometimes,’” Lillian writes in Chapter Five. “But I wouldn’t be my mother…There was no regret for me and these fire kids yet” (p. 94). How does the book depict this cycle of parents raising children, and then children becoming parents themselves?

- Throughout the book, isolation and loneliness take many forms. What are some of the ways that characters experience/navigate their loneliness? Can you think of any characters who didn’t experience loneliness and/or isolation? Were there any characters whose experience of isolation or loneliness surprised you?

- Lillian and Madison have a complicated relationship that veers from deep affection to intense rivalry, from bitter resentment to uneasy allies. Would you characterize their relationship as a “friendship”? Why or why not? Does their relationship mimic in certain ways any relationships in your own life? Do you think their relationship will live on after the events of the novel?

- “People who are strong and in power find weakness repulsive. They don’t want to be around it” writes Wilson (p. 262). We see this in the twins’ father, Jasper. Do you agree with this statement? What do you make of Jasper’s behavior? Have you seen this relationship between power and weakness play out in your own lives in some way, and/or in our society?

- In an essay at the end of the book, Wilson writes about his experiences with anxiety that informed his narrative. “Creating a story is a way for me to connect to the world—to situate my anxiety in a way that can be understood and that I can move forward from” (p. 260). What activities or practices help you connect to the world and/or calm your anxiety? How do they do so?

- Does Lillian come to love Roland and Bessie? When she first got to know them, she described her feelings as more of a “tenderness” for them (p. 81). Meanwhile, she confesses to Madison that she loves her, has always loved her (p. 204). What does it mean to Lillian to love? To be loved?

- Imagine if this story continued years into the future. How might you describe the ongoing lives of Lillian and the twins? What about the lives of Madison, Jasper, and Timothy? What is it about each character that will most influence their future, do you think?