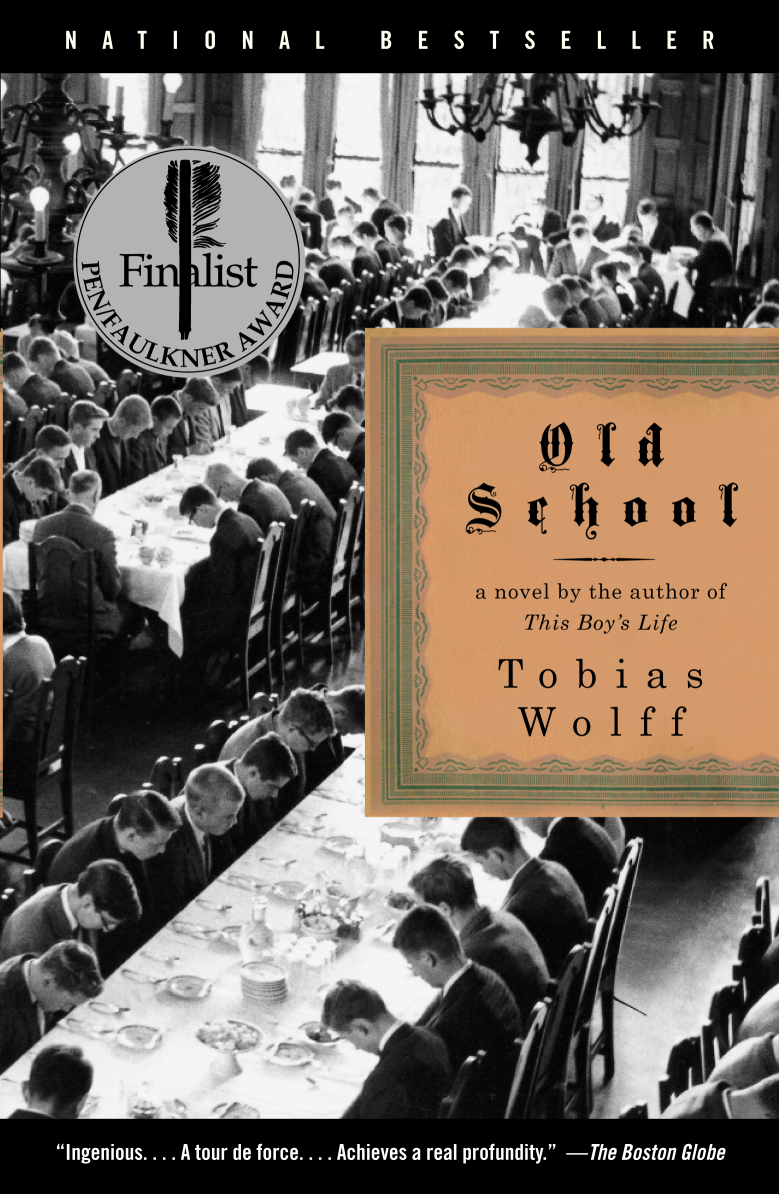

Old School

Overview

Tobias Wolff's Old School is the story of an ambitious, idealistic, and insecure teenager who makes a serious mistake and eventually inherits the consequences. Wolff's unnamed narrator seems so very real that it is hard at times to remember that the book is fiction. The gripping plot has the unpredictability of real life—by turns funny, alarming, satiric, and sad—as well as the moral weight of lived experience. With writers like Tobias Wolff at work it's easy to be optimistic about the future of American literature.

"There is a need in us for exactly what literature can give, which is a sense of who we are… a sense of the workings of what we used to call the soul." —from Stanford Today interview

Overview

Tobias Wolff's Old School is the story of an ambitious, idealistic, and insecure teenager who makes a serious mistake and eventually inherits the consequences. Wolff's unnamed narrator seems so very real that it is hard at times to remember that the book is fiction. The gripping plot has the unpredictability of real life—by turns funny, alarming, satiric, and sad—as well as the moral weight of lived experience. With writers like Tobias Wolff at work it's easy to be optimistic about the future of American literature.

Introduction to the Book

It is November 1960, and the unnamed narrator of Tobias Wolff's Old School (2003) is in his final year at an elite Eastern prep school. Proud of his independence but trying to fit in and advance himself, he conceals the fact that his ancestry is partly Jewish. Eventually, he—and we—discover that almost everyone on campus has some closely guarded secrets.

Every year, the school invites three famous writers to visit and give a public talk. In anticipation of these visits, senior students submit their own poems or stories to a competition, and the author of the winning submission is granted a private interview with the writer. One of the novel's most intriguing elements is the presentation of these writers—Robert Frost, Ayn Rand, and Ernest Hemingway—and its shrewd, penetrating assessment of their works and personalities.

The lives of the narrator and his friends revolve around these visits, and the competitions produce pressures and strains in their relationships, raising issues of honesty and self-deception. In his zeal to win an audience with his idol, Hemingway, the narrator will plagiarize someone else's work, an action with profound consequences—and not for him alone. In the end, we find out what he has made of his life many years later, and what has happened in the lives of some classmates and teachers. A surprising final chapter enriches our understanding of the novel's deepest meanings.

Another of Old School's many pleasures is the way it conveys the significance of literature to our lives, raising fundamental questions of who we are and how we live. As one of the English teachers says, "One could not live in a world without stories… Without stories one would hardly know what world one was in."

The unsparing but sympathetic insight of Tobias Wolff's acclaimed short stories, the emotional honesty and directness of his classic memoir This Boy's Life (1989), and the precise, elegant craftsmanship that characterizes both his fiction and nonfiction—all these qualities come together to make Old School one of Wolff's most satisfying books.

"One of the things that draws writers to writing is that they can get things right that they got wrong in real life by writing about them."

—Tobias Wolff in an interview with Dan Stone

Major Characters in the Book

The Narrator

An outsider in the cloistered East Coast world of the prep school he attends, Old School's unnamed narrator wants desperately to belong. His literary ambitions will bring him the distinction he craves, but in a very different way from what he had imagined.

Bill White

Bill is the narrator's roommate. Along with their passion for writing, the two boys share the unspoken secret of their Jewish heritage. Bill has another secret, one that haunts him more and more throughout the novel.

Jeff Purcell

Another classmate and friend of the narrator's, he has a privileged, upper-class background. Proud, stubborn, and frequently contemptuous of everything and everyone, he nonetheless has a fundamental core of decency and generosity of spirit.

Robert Ramsey

One of the English teachers, Mr. Ramsey is disliked by many of his students. However, by the end of the novel the narrator sees him as compassionate and wise.

Susan Friedman

Susan is the author of the story that the narrator plagiarizes. When he finally meets her, he finds her to be "an extraordinary person," and she shows him a very different perspective on some of the things most important to him.

Dean Makepeace

A "regal but benign" figure to the narrator, the Dean seems remote and assured. But his personal crisis of integrity underscores some of the novel's deepest themes.

Three of the most famous American writers of the 20th century appear, directly or indirectly, as characters in Old School:

Though born in San Francisco, Robert Frost (1874–1963) is forever associated with New England, the setting for most of his life and work. Quietly dazzling in their technical perfection, his enormously popular poems, such as "Mending Wall" and "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening," subtly explore the depths of nature and humanity.

Russian-born Ayn Rand (1905–1982) was the controversial author of a number of philosophical works and two bestselling novels, The Fountainhead (1943) and Atlas Shrugged (1957). Her writings expound her philosophy of Objectivism, which emphasizes rationality and self-interest. It also rejects religion, altruism, and all forms of social collectivism.

Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961) was arguably the most influential American novelist and short-story writer of the 20th century. Renowned for their unique style, such masterpieces as A Farewell to Arms (1929) and The Old Man and the Sea (1952) brilliantly evoke the physical world and the experience of the senses, and stress themes of courage, stoicism, and the need to be true to oneself.

"Our school was proud of its hierarchy of character and deeds. It believed that this system was superior to the one at work outside, and that it would wean us from habits of undue pride and deference. It was a good dream and we tried to live it out, even while knowing that we were actors in a play, and that outside the theater was a world we would have to reckon with when the curtain closed and the doors were flung open."

—The Narrator in Old School

Plagiarism

The narrator of Old School is found to have won the interview with Ernest Hemingway by submitting someone else's short story as his own work. This act of plagiarism is met with dismay and anger by the school's administration and sets in motion a chain of events that has a significant effect on the lives of more than one character. To understand the full importance of this situation in the novel, one must have a clear awareness of what plagiarism is and why it is such a serious matter.

Anyone can recognize the flagrant dishonesty involved in passing off as one's own work something in fact written by someone else. Most of us realize that a piece of writing—whether imaginative or intellectual—is a form of property, and that its owner/creator is entitled to whatever credit and profits his or her efforts and talents might generate.

Yet it is all too easy, when copying snippets of someone else's ideas and even someone else's very words, to succumb—as the narrator of Old School does—to the notion that we have somehow made them our own, that mere appropriation is a form of authorship. Modern technology has made this even easier. Instantaneous access to the infinite amount of material available on the Internet creates the impression that ideas and words are all just there for the taking, especially when all one needs to do is highlight, copy, and paste.

But theft is still theft and fraud is still fraud, no matter the scale. Anyone who uses another's thoughts without proper attribution to the source has stolen that person's intellectual property. Even when proper attribution has been given, using the actual wording of the source material without identifying it as direct quotation is perpetrating a fraud.

Teachers are also upset when their students appropriate the work of others because such an act makes a disturbing statement about the offender's values. If those who would never dream of stealing another's belongings have no compunction about taking someone else's written work, they are saying—whether they realize it or not—that they have less respect for ideas and how they are expressed than for material possessions.

"Make no mistake, he said: a true piece of writing is a dangerous thing. It can change your life."

—The Narrator in Old School

- The dedication of Old School reveals something of how Wolff might feel about his own education. If you wrote a book, would you dedicate it the same way?

- What does the epigraph of Old School, a passage from a Mark Strand poem, mean? How does it relate to the novel's thematic concerns?

- Why do you think Wolff left the narrator and even the school unnamed?

- In Chapter One, the narrator maintains that his school disregarded issues of wealth and social background and judged its students entirely by their actions. Does this turn out to be true? How does his school compare to your own?

- Early in the novel, the narrator says that his aspirations as a writer "were mystical. I wanted to receive the laying on of hands that had written living stories and poems, hands that had touched the hands of other writers. I wanted to be anointed." What does he mean by this?

- Which of his classmates does the narrator feel closest to, and why?

- How do the narrator's changing attitudes toward his grandfather demonstrate his process of maturing?

- Discuss the portrayals of Robert Frost, Ayn Rand, and Ernest Hemingway. How does each influence the narrator?

- Why might Chapter Six be titled "The Forked Tongue"? What are the larger implications of its very last sentence?

- Why does Mr. Ramsey show such disdain for the use of the word "honor"? Do you agree with his attitude?

- Over the course of the novel, the narrator writes two letters to girls. The circumstances differ, but he has the same reaction after sending each letter. What does this pattern of behavior reveal about his personality?

- Why is the narrator shocked by Susan Friedman's attitude toward her own story, and toward writing in general? How valid is his unspoken response to her comments?

- Why does the narrator feel such love and loyalty for his school, despite his final punishment?

- The last sentence of the book is from the New Testament parable of the prodigal son (Luke 15:11-32). How might these be "surely the most beautiful words ever written or said"?