Our Town

Overview

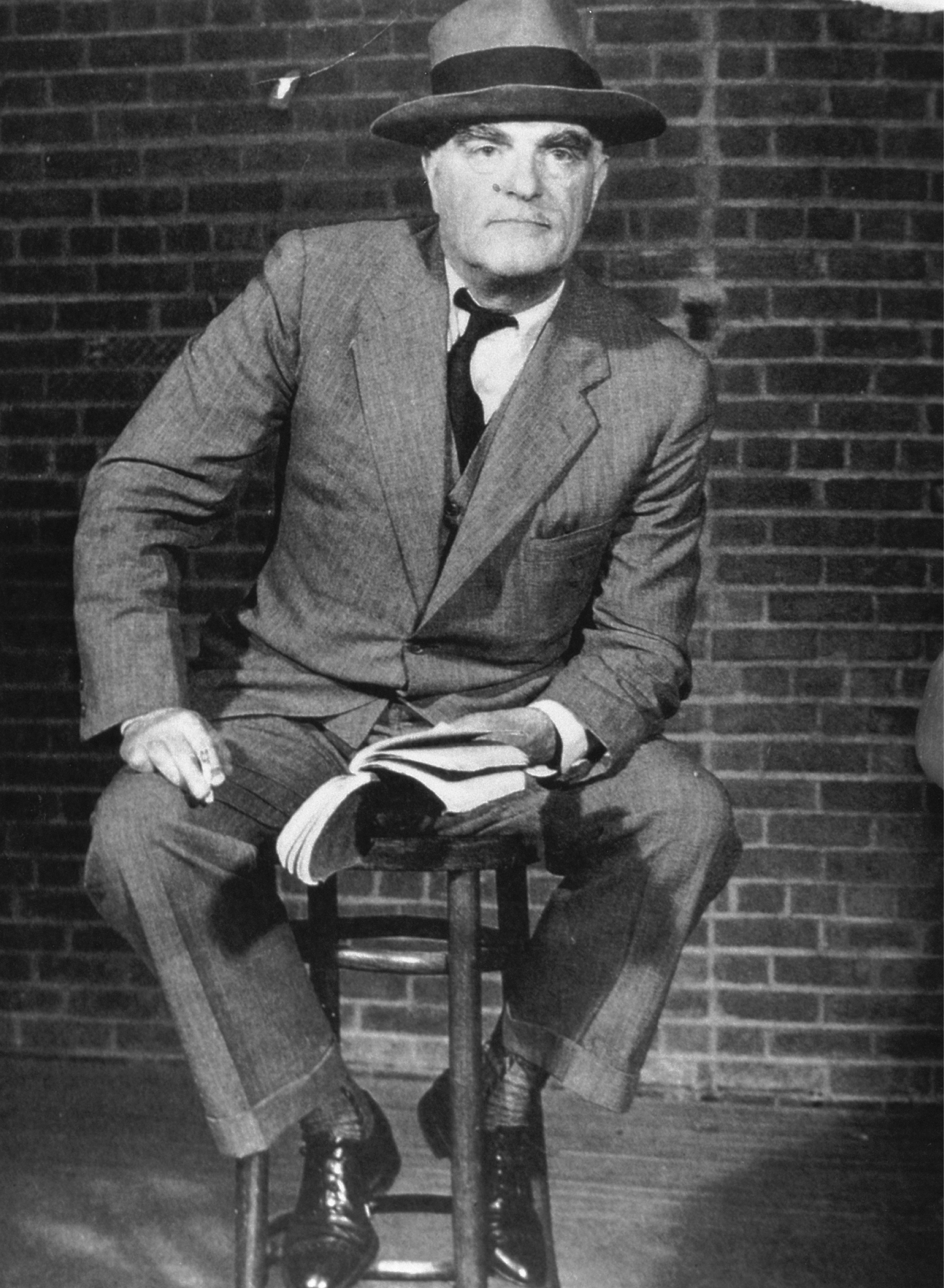

Three-time Pulitzer Prize-winning author Thornton Wilder began his storied career as a novelist before branching out to short stories, screenplays, and dramatic works. At first glance, his play Our Town appears to be a simple, innocuous portrait of life in the small New Hampshire town of Grover’s Corners. But as time passes in the three acts—an ordinary day, a wedding, a death—the play builds to a soaring exploration of human existence: its boundless trials, joys, questions, certainties. This play “is one of the great democratic products of American literature. It gives you the sense that the same profound and horrible truths hold true whether you’re a sophisticate in Paris or a farmer in Grover’s Corners” (acclaimed writer Tom Perrotta in the Atlantic).

"It is an attempt to find a value above all price for the smallest events of our daily life.” —Thornton Wilder on Our Town

Introduction

“The morning star always gets wonderful bright the minute before it has to go,—doesn’t it?”—the Stage Manager in Our Town (p. 4)

Thornton Wilder’s stage drama Our Town (1938) takes place between 1901 and 1913 in Grover’s Corners, New Hampshire, a community that has not produced anyone very “remarkable” (p. 6). The townspeople know many pleasures: seeing the sun rise over the mountain, noticing the birds, watching for the change of seasons. Wilder wanted the play to show “the life of a village against the life of the stars,” he said in an early preface to the book, and to explore “the trivial details of human life in reference to a vast perspective of time, of social history and of religious ideas.”

The audience encounters Grover’s Corners through the point of view of the Stage Manager—a character in the play who functions as the narrator and a sympathetic director. While he sometimes talks directly to the actors, he maintains his distance; most of his lines are delivered as an address to the audience. He tells the audience that the play will show “people a thousand years from now” that “this is the way we were: in our growing up and in our marrying and in our living and in our dying.” The three acts mostly follow two characters, Emily Webb and George Gibbs, who go to school together in Act I, marry in Act II, and experience tragedy in Act III. The play’s opening stage directions are clear and radical, especially for 1938: “No curtain. No scenery.” The costumes are simple; the lighting instructions, complex.

On January 22, 1938, the first performance of Our Town took place at the McCarter Theatre in Princeton, New Jersey. The first New York performance occurred soon thereafter—a now-famous production at the Henry Miller Theatre directed by Jed Harris. Widely produced abroad, this Pulitzer Prize-winning play is not only an American classic but a classic of world literature.In Emily's final epiphany—wisdom she has learned through suffering—we seem to hear Thornton Wilder's voice speak to us: "Oh, earth, you're too wonderful for anybody to realize you."

Major Characters

The Stage Manager is the play’s narrator, who both directs the play and addresses the audience. Always descriptive, sometimes didactic, often funny, he begins the play on May 7, 1901, and ends it twelve years later in the summer of 1913.

The Webb Family

Mr. Webb is the publisher and editor of the town newspaper, the Grover’s Corners Sentinel.

Mrs. Webb’s dour demeanor contrasts with her beautiful garden of sunflowers and her maternal devotion.

Emily, the brightest girl in Grover’s Corners, dreams of living an extraordinary life. In Act II, she marries George Gibbs after realizing that his opinion means more to her than anyone else’s.

Wally, the Webb’s youngest child, dies after his appendix bursts while on a Boy scout camping trip.

The Gibbs Family

Dr. Gibbs is the town doctor. He will die in 1930; the new hospital will be named after him.

Mrs. Gibbs, Dr. Gibbs’s wife, dies from pneumonia during a visit to Ohio.

Even as a teenager, George Gibbs wants to be a farmer and marry Emily.

Rebecca Gibbs, George’s older sister, marries and leaves Grover’s Corners for Ohio.

Other Townspeople

When the play begins, Joe Crowell is the town’s 11-year-old newsboy. He later gets a scholarship to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Simon Stimson, the organist at church who secretly drinks too much, “has seen a pack of trouble.”

-

How would you describe Grover’s Corners, New Hampshire? How is it like or unlike the place where you grew up?

-

In Act I, Emily’s successful speech at school on the Louisiana Purchase encourages her dreams of greatness, and she tells her mother that she “wants to make speeches all [her] life” (p. 31). How is that goal realized? How is it not?

-

In Act I, the Stage Manager mentions that a new bank is being built in Grover’s Corners, and that certain items will be “put in the cornerstone for people to dig up… a thousand years from now” (p. 33). What items do they put in the cornerstone, and what do you think these items will reveal to future generations about the people of Grover’s Corners? If you were to build a time capsule, what would you include and why?

-

The Stage Manager introduces Act II as “Love and Marriage” (p. 48). Why does he choose to draw attention to one particular conversation between Emily and George? What does the scene reveal about Emily and George’s relationship, and what do you think it suggests about love?

-

Discuss the portrayal of marriage in Our Town, comparing the marriages of Mr. and Mrs. Webb and Dr. and Mrs. Gibbs. What do you think Mrs. Webb means when she says that sending girls into marriage is “cruel” (p. 76)?

-

If you were in charge of the play’s lighting, how would you direct Emily’s return to Grover’s Corners in Act III—as a realistic scene, or as a dream?

-

Simon Stimson opines in Act III, “That’s what it was to be alive. To move about in a cloud of ignorance... To spend and waste time as though you had a million years” (p. 109). Do you agree? Why or why not?

-

What understanding has Emily come to when she asks the Stage Manager, “Do any human beings ever realize life while they live it?—every, every minute?” Did this scene resonate with any experiences you’ve had in your own life?

-

Our Town accelerates time, looking back and forward at major events while also describing mundane, daily life. Did the play make you think of the arc of your own life—or your daily routines—in a new or different way? If so, how?

-

If you could revisit one “ordinary day” from your past, which would it be?

-

Our Town breaks the “fourth wall” of conventional theater, blurring the lines between actor and audience. Can you think of any particularly memorable examples of this? Why do you think Wilder chose to include these moments in the play? Did they affect your perception of the story and its themes?

-

Why do you think Wilder chose to tell this story in the form of a play? Do you think your experience of the narrative would have been different had you encountered it as a novel? As a collection of short stories?